Tragedy at sea.

A missing yacht.

A desperate search in the lonely waters of the North Atlantic.

What follows is a tale of loss, longing and redemption. And how a community came together to solve a crisis.

Our story begins in May of 2022, when a German couple advertised for a crew to help them sail their CNB 66 yacht from Bermuda to Nova Scotia. Finding two experienced sailors, they set sail in early June, on what should have been a few days of pleasurable cruising up the eastern coast of North America.

But two days into the voyage, the yacht ran into unexpected bad weather. While adjusting the sails, a boom swung loose and badly injured one of the owners. When her husband ran to provide aid, he was also struck and badly hurt. While the two crew members did their best to render first aid while struggling to control the boat, stormy weather pushed the vessel several hundred miles away from Halifax – and out of range of Canadian and U.S. rescue helicopters.

Eventually, with the help of a U.S. Coast Guard cutter that acted as a floating refueling point, a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter managed to winch aboard the stricken couple, and transport them to a Massachusetts hospital. But the injuries were too severe, and the husband and wife passed away.

With difficulty, the two crew members managed to rendezvous with a U.S. Coast Guard cutter, which took them aboard and secured the yacht. But that left the vessel unmanned and adrift hundreds of miles offshore.

Yet the story doesn’t end there.

The deceased couple had been sailing around the world, and had kept their family keepsakes with them. Naturally, their son wanted to recover those cherished possessions from the yacht.

A Small Yacht In A Big Ocean

But where exactly was the yacht?

The son contacted a German insurance company, which then contacted LeeWay Marine, a Nova Scotia maritime services provider – one of whose owners happened to know Ben Garvey, president of Halifax-based engineering firm Enginuity.

Garvey was about to take his family on vacation, but he knew what he had to do. “I called the connections that I had in the industry and said, ‘We need a boat,’” recalled Garvey. “A boat with a very experienced crew who are going to be subtle, who are going to be sensitive. Because you’ve got a $3 million asset floating around out there which is fair game. Anybody could go put a line on it and salvage it.”

Nor was outside salvage the only threat. A vessel adrift off the Halifax coast would be in the middle of busy shipping lanes, which risked a collision at sea.

Garvey quickly found a fishing boat that could be pressed into service as a rescue craft, as well as an experienced crew. But after three days of fruitless searching, Garvey decided that more help was needed. “I said, ‘We really need to get a plane up there. That’s the only way we can cover this. With only a fishing boat, you’re only going to see 40 miles either side even with its radar, and it’s just going to be a matter of luck.”

To cover a vast search area, the aircraft would need to have long range and be equipped with sophisticated sensors. That meant the sort of maritime patrol planes usually flown by governments. But with time running short, Garvey had an idea.

A Search Plane With No Ordinary Crew

“I knew there was only one company doing that here in Nova Scotia,” he said. That company was PAL Aerospace. PAL has extensive experience assisting the Canadian and other governments with maritime patrol work, including search and rescue, border security, drug interdiction, and Intelligence Surveillance Reconnaissance (ISR) missions.

Garvey contacted CarteNav, a PAL subsidiary that makes airborne sensor integration systems such as AIMS-ISR, and thus had plenty of experience in maritime search. This brought in Jens Lundgreen-Nielsen, a former Danish F-16 pilot and then PAL Aerospace’s Vice President of Aerospace Operations.

Lundgreen-Nielsen scrambled to find a suitable aircraft and crew on short notice. He did manage to find a PAL test aircraft that was available. Locating a crew was harder.

“We didn’t have any spare crew,” remembered Lundgreen-Nielsen. “But we did have a group of the management team who all volunteered. They ran home to get the required sleep and off-duty time to be legal to go fly, and then reported back in for a 2 a.m. takeoff.”

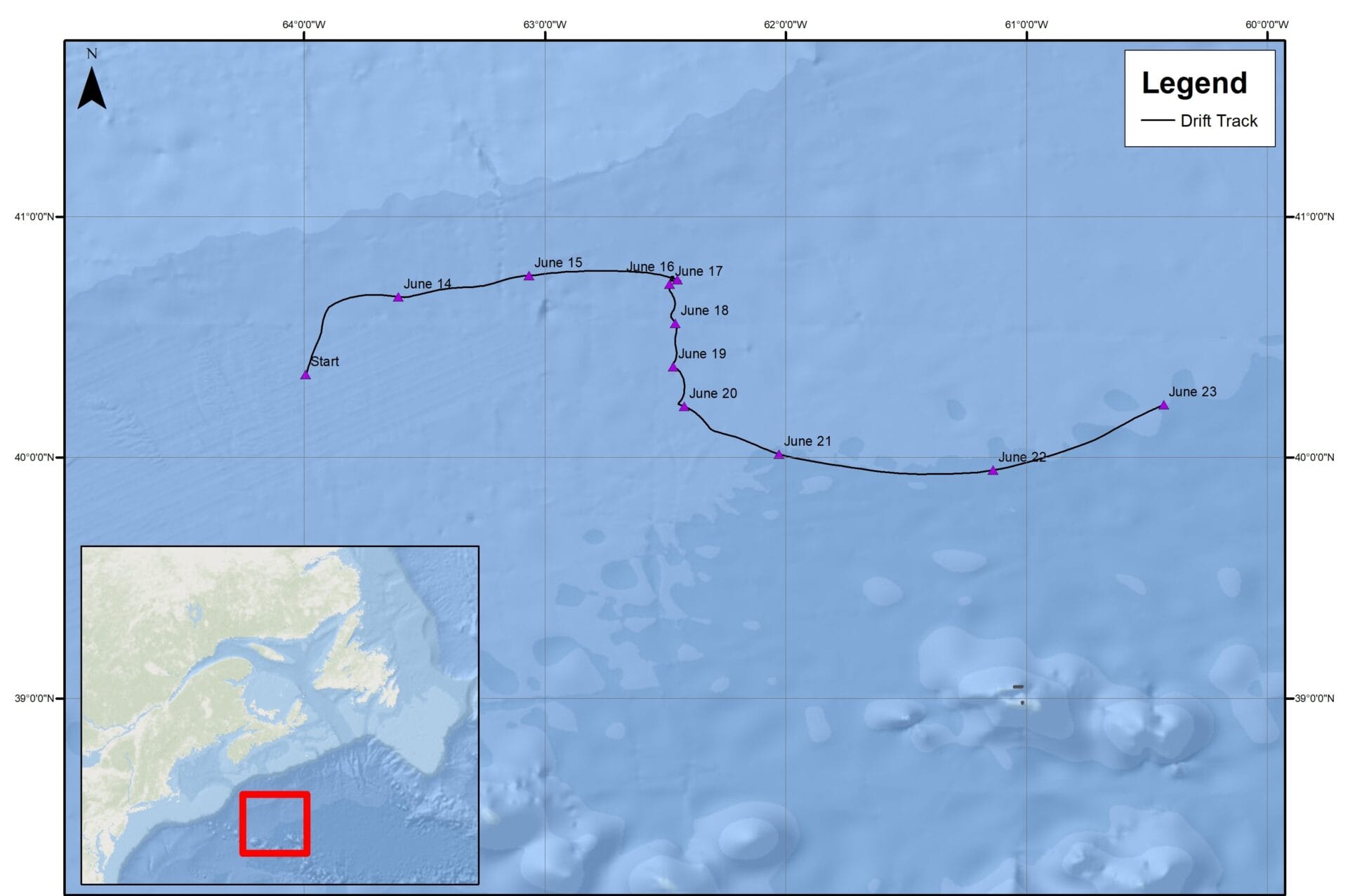

Now the searchers had a boat and a plane. That still left the exact location of the yacht a mystery. The last reported positional data – which was certainly out of date by now — suggested it was several hundred miles southeast of Halifax. But that still left a lot of ocean to cover. Finding an abandoned 66-foot yacht, at the mercy of current and wind, would be like finding a needle in the vast haystack of the North Atlantic.

Modeling Comes To The Rescue

Again displaying its resourcefulness, PAL turned to an unexpected asset. Among the work the company does is to predict the path of icebergs that could pose a hazard to shipping. To make these predictions, the company had developed mathematical models to chart the expected course that icebergs would take.

If these models could accurately predict drifting blocks of ice, then why not an abandoned boat?

Because an aircraft is an expensive asset to fly, we pride ourselves on having very accurate data that we turn into actionable intelligence. And so, when the aircraft gets onto a location, we have already told it, ‘Okay, here are your probabilities. Here is your best bet to find the target is you're looking for.’ Then the experts on the aircraft use this to come up with the optimal search pattern.

However, modeling and simulation is often as much art as science. There are numerous variables that could affect a vessel’s course and location. “We have to consider wave, current, and wind all acting in separate directions on this target,” Green said. “And we plug that into a numerical model, and then look at it and ask, ‘does this make sense?’”

Fortunately, PAL had both well-developed models based on solid data. “We have a very good database of the weather in terms of the wind and the waves, and we looked at several high-resolution numerical models for that,” said Green. “And we have very good data on currents from the Canadian government that we utilized.”

To use iceberg models to predict the movement of a yacht required a bit of creativity: Ryan Crawford – Data Analyst, IES at PAL Aerospace along with the Special Missions/ AMSD team, used a model of an iceberg flipped upside down to simulate the behavior of the vessel. Yet the biggest variable in these models was whether the yacht was still under sail, which would greatly affect its course and speed. Ryan, Green and team had to make an educated guess. “We knew that this was a sailboat that is 66 feet long, a keel maybe 15 to 20 feet high, and a mast that could be 65 feet high. Then we thought about it, and decided that the sails must have been down. The Coast Guard had removed the crew, and the first thing they would have told the crew was to put down their sails, because the helicopter couldn’t lower a rescue team while the sails were up.”

A Gamble That Succeeded

By the evening of the fifth day, the search boat was in the area recommended by PAL’s models, while the PAL search aircraft was preparing to take off at 2 a.m. the next morning. “They told us to head to this area, because the plane was going to arrive there at first light,” Garvey said.

However, before the aircraft took off, news arrived that the yacht had been found. “Our boat got there about 2:30 a.m.,” said Garvey. “And there was the yacht. Exactly where was it supposed to be.”

Garvey, who was on shore coordinating the effort, got the first call from the search vessel. “The guys on the boat were as excited as kids. I could hear them whooping and yelling.”

And not a moment too soon to avoid a potential disaster. “When they boarded the vessel, they looked up and there were four ships within a mile of their location,” said Garvey.

In hindsight, even though the yacht was located before the search aircraft was launched, Garvey believes that a combined naval and air search is the best response to this kind of situation. “I think we should have jumped to a flight option immediately. We should not have sent a boat out without a plane first, because the position data was too old.”

In the end, a recovery crew sailed the yacht back into port, and a grateful son got back the keepsakes of his beloved parents. Two people had tragically lost their lives, but at least there was closure for the family. And a lesson in how people can surmount even the most difficult challenge when they pool their talents and resources.